In Thread and On Paper: Anni Albers in Connecticut | Curator Interview

A Conversation with exhibition curator Fritz Horstman, the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and Lisa Williams, Associate Curator, NBMAA

Known for her pioneering graphic wall hangings, weavings, and designs, Anni Albers (1899-1994) is considered the most important textile artist of the 20th century, as well as an influential designer, printmaker, and educator. Organized by the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, In Thread and On Paper: Anni Albers in Connecticut explores the groundbreaking work and writing Albers produced in Connecticut from the 1950s through the end of her life, and includes an extensive body of textiles, wall hangings, commercial collaborations, and works on paper. A landmark presentation, In Thread and On Paper is the first museum exhibition dedicated exclusively to the artist’s incredible output in the 44 years she lived in Connecticut. In the following conversation, exhibition curator Fritz Horstman of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and NBMAA Associate Curator Lisa Hayes Williams discuss Anni Albers and the evolution of this remarkable exhibition.

Lisa Williams: Fritz, thank you for joining me in a conversation about In Thread and On Paper, a beautiful exhibition that has, in some respects, been years in the making. You and I first connected in 2017, during an NBMAA staff trip to the Albers Foundation in Bethany, Connecticut—a visit motivated by our hope and aspiration to work together to celebrate the legacy of Anni and Josef Albers, internationally acclaimed artists who happened to call Connecticut home for many decades.

Over the subsequent years, we have had countless conversations and exchanges about how an exhibition might take shape and what it might comprise. (Freckled with other conversations about music, art, life in Connecticut, and inevitably, knotweed!). The planning of this exhibition has been a phenomenal adventure and fascinating learning process for all of us at the NBMAA, and we were thrilled when our dream to collaborate materialized into In Thread and On Paper: Anni Albers in Connecticut, currently on view at the Museum and online at nbmaa.org. Thank you, Fritz, for all that you and the Foundation have done to make this exhibition possible—as institutional partners and now friends—and for the opportunity to continue our discussions today, curator-to-curator.

Perhaps the best place to start is with the artist herself. Who was Anni Albers and why is she so important, in your perspective?

Fritz Horstman: Thanks, Lisa. You and your team have been wonderful.

Anni Albers is interesting on so many levels. Historically she stands out as one of the great artists to emerge from the German Bauhaus, as one of the first female artists to achieve global recognition, and as a rare artist who simultaneously created work that was both functional and purely artistic. Of course, it is the work itself that explains why we are still thinking about her now. Her understanding of and real empathy for her materials is unparalleled. She was driven by an unwavering curiosity about the way things are made and how simple materials come together to make more complicated objects. A desire to share that curiosity comes through in all of her work.

A more complete biography is on the Museum’s website, but very briefly, after the closure of the Bauhaus in 1933, Anni and her husband, the painter Josef Albers, invited to teach at Black Mountain College, seized the opportunity and moved to the United States. In 1949 she had one of the first solo exhibitions of a female artist at MoMA (which was organized by another Connecticut resident, architect Philip Johnson). It was also the first solo show by a weaver at that museum. A year later, the Alberses moved to Connecticut when Josef started teaching at Yale. Anni continued weaving for another twenty years, before transitioning to printmaking, which she pursued nearly until the end of her life in 1994.

LW: In Thread and On Paper represents a number of significant “firsts”: it is the first solo exhibition of Anni’s work at a U.S. museum in 20 years, as well as the first show to focus exclusively on her 44 years in Connecticut. What made it possible to assemble this landmark presentation here and now, and how might it change the world’s understanding of Anni’s life and work?

FH: Earlier you described how we met and the evolution of the idea for the exhibition. Once we had agreed that including Anni in New Britain’s 2020 exhibitions calendar, the opportunity to focus on her work in Connecticut took hold and wouldn’t let go. The subject fits perfectly with the Museum’s context and the Albers Foundation’s mission. There is a great interest right now in all things Bauhaus, having last year celebrated the 100th anniversary of its founding. That paired with the vital and belated increase in interest in art made by women has turned a lot of people’s attention towards Anni. It could also be said that she is simply finally receiving her due. Whatever the case, it has resulted in a number of critically acclaimed major solo exhibitions and retrospectives of her work, notably at the Guggenheim Bilbao, London’s Tate Modern, K20 in Dusseldorf, and at David Zwirner Gallery in New York.

Very early in the process of organizing the exhibition we made sure we would be able to include two of her pictorial weavings–some of her most sought-after work. With those loans from the Albers Foundation in place, the rest of the exhibition was a matter of telling the story in the most compelling way.

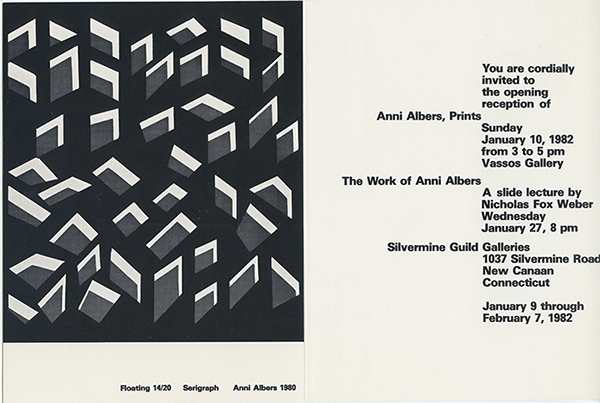

More than in some other recent exhibitions, here we see Anni not only as an amazing weaver and printmaker, but also as a person, as a resident of New Haven and later Orange, Connecticut. Photographs from openings accompany invitations to exhibitions she had at other nearby museums and galleries. The 44 years she lived in Connecticut were the most productive years of her artistic life, and the most varied. Drawing attention to the significant developments she made relatively late in life provides a new angle from which to view her career.

LW: This show takes place as part of the Museum’s 2020/20+ Women @ NBMAA initiative, in which all of our exhibitions throughout 2020 have been dedicated to female-identifying artists, in an effort to bring greater representation of women to our galleries. Anni’s gender impacted the direction her work took early on, as well as her ability to teach (or not) after her husband was hired at Yale. Despite these obstacles, she nevertheless achieved tremendous success and acclaim. How was Anni able to maneuver around deeply ingrained biases against women artists during her lifetime?

FH: When Anni was placed in the Bauhaus’s weaving workshop, which had been established a few years earlier as an outgrowth of the women’s department, she was at first disappointed. She never spoke about the gendered aspect of that situation, but instead remembered that she thought thread was a “sissy” sort of art material. Nevertheless, the threads soon captured her imagination, and she ran with them. The Bauhaus was one of the first art schools in Europe to accept both women and men. The women who were there would have been very aware that most of them had been placed in the weaving workshop, but it is unlikely that many of them would have seen that as an aberration from their experiences in the world up to that point. This is not to say it was correct, only to contextualize.

Years later, when Josef was hired by Yale, Anni found herself for the first time in many years without formal teaching responsibilities. I have been told that Yale had a rule then that spouses of faculty weren’t allowed to teach. If such a rule existed it almost certainly was aimed at keeping wives out of the classroom. Nevertheless, Anni was invited to give “unofficial” lectures in the School of Architecture.

The Alberses were both resolutely non-political. They considered art to be more important than anything related to politics, and since they had devoted their lives to art, they didn’t give much attention to anything else. Perhaps that devotion in some way allowed Anni to make the work that she did despite the obstacles and biases in society. She didn’t consider herself a feminist, as that was political. She was an artist, first and foremost. She loathed careerism. That said, she was too smart to have not seen the lay of the land, and in her quiet way, rearranged it to make room for herself.

LW: Anni is recognized for her fearlessly experimental and visionary approach to her work, in which she married ancient weaving techniques and traditional materials with cutting-edge technology and modern design. She is also celebrated for her democratic engagement with art and craft on equal terms. What do you believe are some of the most groundbreaking and innovative aspects or examples of her work?

FH: The textile artist Jack Lenor Larsen referred to Anni Albers as a "visionary" when he presented her with the American Craft Council’s Gold Medal in 1981. She responded in a letter to Larsen: “As to name calling, instead of visionary, I suggest experimenter.” It was that experimentalism, which was perfectly natural for her, that led others to find her work so groundbreaking. Perhaps her most significant contribution was helping to raise the status of weaving from being relegated to only craft to being considered an art form, on par with painting or sculpture. To help us understand her intention, she denoted some of her work as “pictorial weavings,” indicating that they are to be seen only as art, and not to be used as designs for placemats or bedspreads.

LW: We were thrilled at the opportunity to present two of Anni’s pictorial weavings in the show--Black, White, Gold I, 1950 and Two, 1952--given their rarity as well as their significance in Anni’s output in Connecticut. Can you elaborate on the distinctions between Anni’s pictorial weavings, versus her textiles and wall hangings?

FH: We’re getting into somewhat confusing terminology here, made perhaps more so by Anni’s fluid movement between techniques and applications. Textile is a broad category that includes weaving, tapestry, and other cloths.

A wall hanging may simply be a fabric that is to be draped on a wall as a form of decoration. Anni’s pictorial weavings and wall hangings are all textiles made with an artistic intention. In the 1970s and early ‘80s she designed several textiles for the companies Sunar, S-Collection, and Knoll. Not designated as pictorial weavings, these were mass-produced, and in different cases may have been intended for specific uses—curtains, upholstery, and so on. In the exhibition we have hung nine of them from the ceiling, creating a sort of ethereal fabric cloud, intentionally blurring the line between art and functional fabric, much as Anni did with so much of her work.

LW: One of the most fascinating objects in the exhibition is Anni’s own loom—perhaps the very one, as you mentioned at one point, with which she created her incredible pictorial weaving Black, White, Gold I, 1950. I was astounded to learn how involved and labor-intensive the preparation of a loom could be. Can you describe some of the steps that Anni would have taken to prepare her loom for weaving?

FH: This is a bit complicated, but in the very simplest sense, a weaving is a pliable plane made up of vertical threads interlaced with horizontal threads.

Setting up a loom requires first arranging all of the vertical threads, known as the warp. Each warp thread must be carefully measured and then threaded through the loom’s mechanisms in an order set by the weaver. That order determines what patterns will be possible on that particular warp. Once all of the warp threads are in place, they are pulled into tension. All of that takes many hours, sometimes days for more complicated patterns. With the warp in place the weaver sets about interlacing with horizontal threads, known as the weft. The loom is able to lift different warp threads, as determined by the way the warp was laid out. When only some warp threads are lifted, while others are not, a space is opened between them. The weaver passes the weft through that space on a device called a shuttle, making one row. The raised warp threads are lowered and a different group of warp threads are lifted. The shuttle passes through again, leaving another row of weft. This process is repeated hundreds of times, slowly building up a weaving.

LW: Thank you for articulating this complicated but incredibly elegant process so clearly! I think visitors will find it interesting to explore in the exhibition how, in Anni’s later years, she shifted away from the very labor-intensive process of weaving to printmaking, which opened up a whole new world of creative possibility for her. Perhaps, however, this is a perfect moment to address the interactive stations in the exhibition, including the large-scale weaving wall that offers visitors an opportunity to gain hands-on weaving experience. Can you describe the interactive aspects of the show, and what you hope visitors might learn from them?

FH: We learn so much with our hands, so why not let people touch? Textiles, of which there are many in the exhibition, call out to be touched.

Unfortunately, that isn’t possible in most of the exhibition. We built a large weaving wall, on which visitors can try their hands at actually weaving, using materials very much like those Anni used. Over the course of the exhibition the community will create a large weaving.

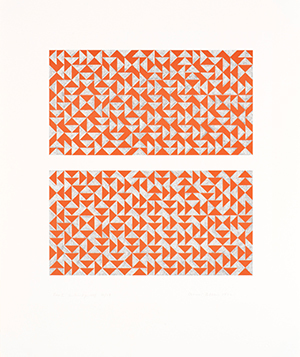

Another station comprises a large table with a grid cut into its surface. Plastic triangles of the same size as the grid are available for visitors to manipulate, experimenting to recreate patterns like Anni’s, or to come up with something completely new. Graph paper and pencil was the starting point for much of Anni’s artistic output. This large-scale version of that allows visitors to experience the incredible range available in such a simple format.

Anni’s loom, which is one of the first objects one sees when entering the exhibition, will be activated during the exhibition at specific time by invited weavers. They will produce replicas of some of the small textile samples that Anni made, which fill the vitrine cases near the loom. (images in ‘sample’ folder) Visitors to the exhibition will be invited to touch and handle the completed reproduction samples, they will be made available for visitors to touch.

All of this is to deepen the visitor’s understanding of the processes and materials with which Anni engaged, and to acknowledge that the sense of touch is as capable of aesthetic enjoyment and enrichment as sight.

LW: The opportunity for collaboration, through visitors’ use of the weaving wall and other interactive aspects of the show, is particularly meaningful, given that collaboration played a significant role in Anni’s creative output. In Thread and On Paper features a number of works, including wallpaper, rugs, and tapestries, that Anni created as commercial collaborations or commissions. Why do you think these opportunities appealed to Anni?

FH: Anni first learned to weave at the Bauhaus, where the different workshops were charged not only with teaching and learning, but also with creating products that could potentially be sold to support the school. The weaving workshop turned out to be the most successful in these terms. That ethic stayed with her for the rest of her career. Creating something that was both useful and beautiful made perfect sense. Her curiosity about process and material was piqued by the opportunity to collaborate and to work in a new medium with new tools and techniques. In the case of the wallpaper, I should be clear that it was made in a collaboration between the Albers Foundation and the company Christopher Farr Cloth using Anni’s designs. It is in her spirit of applying one design to multiple purposes, but created posthumously.

LW: Along those lines, The Glass House in New Canaan is also presenting an exhibition of Anni’s work in 2020 that explores her relationship to, and influence upon, the world of architecture and design. Can you share some insights about the focus of that project?

FH: We’re very excited for the opportunity to collaborate with the Glass House. Anni first met Phillip Johnson, the architect of the Glass House, when he visited the Bauhaus in the 1920s. They stayed in touch for decades, working together on projects several times, including the 1949 MoMA exhibition. The Glass House has started a new series of exhibitions, named Pliable Plane, after an essay Anni wrote in 1957. For the first iteration in the series we are working with a weaver in Germany to recreate some of Anni’s textile samples as bedspreads and window coverings for the transparent pavilion’s sleeping area. There will also be a small exhibition of related work in the neighboring gallery.

LW: Anni’s work drew upon, and in turn influenced, so many different creative arenas—textile design, printmaking, architecture, pedagogy, and writing, among others.

You yourself are an artist, musician, and educator. Can you share if and how some of your own practices informed the curation and installation of the Anni Albers exhibition? Conversely, do you find that your work at the Albers Foundation has influenced the art and music you create?

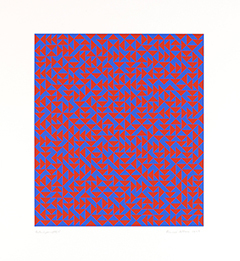

FH: It’s hard to pull those things apart, but without a doubt the way I see the world as an artist, musician and educator influences everything else, including the curation of this exhibition. One area of the exhibition includes around twenty drawings and prints, all of which feature repeated triangular motifs. I can’t help but see in them the syncopations, modulations and timbres of not only a musical score, but in a synesthetic way, music itself. One of my favorite moments of the installation process was creating an arrangement of those pieces that could enhance that musicality, with rests, rhythms and resolution. As an educator, I try to help others to expand their understanding of the world.

In some cases that is sharing knowledge or providing examples. My most rewarding teaching relies on setting up situations for people to make their own discoveries. I’ve included so much hands-on material in this exhibition because we learn with our hands, just as much as we do with our eyes.

When I am writing music or creating art I am rarely thinking about anything other than the material or form of the project. That said, with a little distance I can see that my focus on material and the clarity that I try to bring to my ideas may come out of being so close to the work of the Alberses. It’s incredibly inspiring, and also humbling to be so immersed in the writing, teaching, and art of such incredible minds.

LW: Has developing this exhibition inspired ideas about what you might want to do next, both in terms of your work with the Foundation and in your own artistic practice?

FH: It has been incredible to work with the NBMAA, a museum that is so ready to bring educational material directly into the exhibition. The physical space of the museum has proved fairly ideal for this particular exhibition’s content, and will provide a great example for future projects. The Albers Foundation is working with curators and educators at the Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris where there will be a major double retrospective of both Anni and Josef Albers next year. The educational material we’ve developed with this exhibition will inform and enhance that one, I hope.

In terms of my own art, I’m seeing a lot of triangles in my studio right now. Though they’ve arrived through paper folding and photo processes, I have a feeling Anni’s influence isn’t hard to notice.

LW: Our team learned so much from you during the process of installing the exhibition and enjoyed the process enormously. There were aspects of installation that were particularly impressive to witness, including the hanging of Anni’s large rugs and the series of nine textiles, which required a great deal of pre-planning and calculation to position. Were there any challenges or surprises throughout the planning or installation of the exhibition?

FH: Two walls in the exhibition are covered in wallpaper based on one of Anni’s designs. One of the two patterns had come in two rolls.

Only after it was on the wall did we realize that somehow one of the rolls was printed in the exact inversion of the pattern on the other. Together the effect was dizzying. Given that the wallpaper had been shipped from the UK and that this was only ten days before our opening date, it produced some anxiety, though new paper arrived in time for the issue to be fixed. More interesting was looking at the two versions side by side. It was something that would have fascinated Anni, I’m sure. Though it wasn’t right for the wallpaper, the effect of getting two patterns out of a single design would have appealed to her sense of economy.

Of course, there were many other small surprises. None were nearly as dramatic as the sudden temporary closure of the museum, just three days before the exhibition was set to open, due to COVID-19.

LW: I agree—this was an especially difficult turn of events, given how close we were to opening the exhibition. Although the show was scheduled to open in mid-March, the public has yet to see it, due to our temporary closure as a result of the pandemic--a plight shared by museums across the world. Thankfully, there are some phenomenal online offerings at nbmaa.org/online that the public can access in the meantime, including your wonderful exhibition walkthrough as well as several related lectures. When we are at last able to welcome visitors to In Thread and On Paper, what are three works in particular that they should look for and why?

FH: When it opens, I would send visitors directly to Black, White, Gold I. Its power speaks for itself.

A group of six pencil drawings on graph paper is as close as we can come to seeing Anni’s mind in action. Some of the very last works she made is a series of drawings made using felt tip pens on paper. Late in life she had developed a profound shake in her hands, and just as she would with any other material or tool, she found what was interesting about it. Holding the pen in her shaking hand she let it play naturally across the page, creating lines that are at once like a meandering thread in a weaving, and also like text.

Can I ask you a similar question? What work has particularly captured your attention from this exhibition?

LW: There are so many captivating works in this exhibition, it is difficult to narrow down to a single favorite. However, I think one of the most beautiful moments in the exhibition is the installation of Anni’s Mountainous series of six blind-embossed (or inkless) prints adjacent to the nine hanging textiles she designed for Sunar Textiles. Both the prints and textiles are white monochrome surfaces interspersed with subtle geometric patterning.

Because they are so minimal, the works showcase Anni’s incredibly sophisticated and sensitive mastery of texture, surface, light and shadow, shape, and positive and negative space. They are quiet, but incredibly powerful. As a point of contrast, I also love the experience of color throughout In Thread and On Paper. Although many of Anni’s works utilize monochrome palettes or neutral hues, others seem to absolutely revel in sumptuous color—from dazzling reds and oranges to aquas and deep blues. This is especially evident in the phenomenal sweep of prints you installed in Stitzer Family Gallery, that includes a spectrum of color, as well as Anni’s experiments with metallic paper.

Finally, I’m thrilled that we were able to include a work that Anni created at Fox Press, once located in nearby West Hartford. Can you elaborate a bit on what drew Anni to printmaking?

FH: Anni made her first prints in 1963 and 1964 at Tamarind Lithography Workshop. That experience opened her eyes to the possibilities of the medium. Her lifelong insistence on understanding the fundamentals of process and material was reengaged by the new potentials and limitations inherent to the many processes and materials of printmaking with which she engaged over the next twenty years.

In 1973 Nicholas Fox Weber introduced Anni Albers to Fox Press, his family’s commercial printing shop in West Hartford. Weber, who has been the executive director of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation since 1976, facilitated the production of several prints designed by Albers and printed by Fox Press, including Fox I. Though not typically used for the production of art prints, the machines and technicians at Fox Press presented Anni with a unique opportunity to try something completely new.

LW: Anni and her husband lived through times of tremendous social and political upheaval, including World War II, and found expression and purpose in the work they created. In her writing, Anni so beautifully analogizes material forms and processes to the human experience, and to the productive and healing power of creativity. Against the backdrop of our present moment, I found the following passage especially poignant:

Our world goes to pieces; we have to rebuild our world. We investigate and worry and analyze and forget that the new comes about through exuberance and not through a defined deficiency. We have to find our strength rather than our weakness. Out of the chaos of collapse we can save the lasting; we still have our ‘right’ or ‘wrong,’ the absolute of our inner voice—we still know beauty, freedom, happiness...unexplained and unquestioned.

- Anni Albers, "One Aspect of Art Work," Design 1944

Her writing operates on so many different levels. Are there passages of her writing that you have found especially salient to your perspective and experience, or your outlook on her work?

FH: Anni’s writing is some of the clearest and most concise I’ve read. The quote you’ve included is perfect, especially for our current moment. Two more passages that I find particularly helpful are:

Things take shape in material and in the process of working it, and no imagination is great enough to know before the works are done what they will be like.

- Anni Albers, "One Aspect of Art Work," Design 1944

Beginnings are usually more interesting than elaborations and endings. Beginning means exploration, selection, development, a potent vitality not yet limited, not circumscribed by the tried and traditional.

- Anni Albers, On Weaving 1965

LW: Beginnings are perhaps a perfect place to end. I hope that this show and these conversations are the beginning of many more to come, celebrating Anni Albers and the incredible work that she undertook in Connecticut. Thank you, Fritz, and thanks to the incredibly knowledgeable, generous, and dedicated team at the Albers Foundation, as well as fellow staff here at the NBMAA.

FH: It’s been a pleasure. Thank you for initiating this conversation, and for the invitation to bring In Thread and On Paper to New Britain.

Thank you also to Sam McCune, my colleague at the Albers Foundation, for his incredible logistical support, and to Karis Medina for her time and weaving expertise, as well as to Brenda Danilowitz, John Doyle, Maria Shevelkina, Kyle Goldbach, Amy Jean Porter, Anne Sisco, Jeannette Redensek, Lucy Weber and Nicholas Fox Weber, all of whom were instrumental as the exhibition developed. Though I know that I’ve not met everyone at NBMAA who has helped, thank you, Min Jung Kim, Angel Sherrell, Cynthia Cormier, Maura O’Shea, Lisa Lappe, Javanica Dai, Veronika Zhikhareva, Laura van Dine, and especially to the collections team: Keith Gervase, Mike Mindera, and Gabriella George. Thank you.

In Thread and On Paper: Anni Albers in Connecticut is part of 2020/20+ Women @ NBMAA presented by Stanley Black and Decker with additional support provided by Bank of America.

The exhibition is made possible by the generosity of The Coby Foundation, Ltd.

Exhibitions at the NBMAA are made possible thanks to the support of the Special Exhibition Fund donors, including John N. Howard, Sylvia Bonney, Anita Arcuni Ferrante and Anthony Ferrante, Marian and Russell Burke, and The Aeroflex Foundation.

We also gratefully acknowledge the funding of Brendan and Carol Conry, Irene and Charles J. Hamm and Carolyn and Elliot Joseph.